I. Introduction

Visiting Washington, DC last summer, I did most of my shopping at a neighborhood Whole Foods Market. In Upstate NY, I’ve never shopped at organic food markets like Trader Joe’s or Whole Foods, so having the chance to shop at one of these stores made me feel more environmentally conscious. Although the price of most foods was higher than what I normally pay at home, I didn’t mind putting my dollar towards foods that were organic. Also, I surprisingly ran into a bottle of Red Jacket Orchard Apple Juice made in Geneva, NY.

Visiting Washington, DC last summer, I did most of my shopping at a neighborhood Whole Foods Market. In Upstate NY, I’ve never shopped at organic food markets like Trader Joe’s or Whole Foods, so having the chance to shop at one of these stores made me feel more environmentally conscious. Although the price of most foods was higher than what I normally pay at home, I didn’t mind putting my dollar towards foods that were organic. Also, I surprisingly ran into a bottle of Red Jacket Orchard Apple Juice made in Geneva, NY.  I shouted, “Hey look, it’s from Geneva!” At the time, I thought how great it was that their products had reached as far as Washington, DC. However, after reading Michael Pollan’s section “Pastoral Grass” in Omnivore’s Dilemma, I started to realize how ignorant I might have been…

I shouted, “Hey look, it’s from Geneva!” At the time, I thought how great it was that their products had reached as far as Washington, DC. However, after reading Michael Pollan’s section “Pastoral Grass” in Omnivore’s Dilemma, I started to realize how ignorant I might have been…

Considering the pervasive nature of organic food, you’d be hard-pressed to find anyone who hasn’t been presented with a choice between organic and conventional. From the denizens of Wal-mart browsing for organic Cheerios, to the trendy crowd licking Pinkberry’s frozen yogurt off plastic spoons, it is probable that most of us have even eaten organic produce in one of its countless permutations. But what exactly is organic food?

Is it healthy?

Natural?

Environmentally friendly?

Locally grown?

Does it support small farms?

These are some of the questions that may whirl around your head when you discover the label marking your blueberries a member of this secret society of produce. This secret society is a riddle, inside a mystery, swathed in a tasty organic, whole-wheat, enigma wrap. Myths surround the inscrutable rituals and rites of passage food goes through to become organic.

All this leaves one to wonder how exactly everything from tangerines to Newman-Os came to bear this badge of recognition (and its constant companion, the expensive price tag). We examined our own perceptions of what it meant to be organic during our last class in a tasteful way.

II. What’s Organic?

In class we performed an activity that tested our taste buds, texture, smell and color perception in identifying unknown organics and non-organic foods. There were two samples of each food, A and B, and we individually voted on which food we thought was organic. Here is how we did…

| Food | Number that thought A was organic: | Number that thought B was organic: | Which was Organic? |

| Cookie | 14 | 0 | A |

| Chocolate Chips | 3 | 11 | A |

| Banana | 6 | 8 | B |

| Tomato | 12 | 2 | A |

| Cheese | 3 | 11 | B |

| Broccoli | 2 | 11 | A |

| Apple | 8 | 6 | B |

| Lemon | 0 | 14 | A |

As a class, we could not really tell what the difference was between each organic and non-organic food. However, it is interesting to note that 2 of the students eat more organic than conventional food products, while the other 12 eat mainly conventional products. Despite our dietary differences, no one could correctly discriminate which food was which consistently.

In class we discussed what our perceptions were concerning organically produced food. Many believed that comparing organic foods and conventionally made foods was the same as differentiating between anthropogenic versus natural. Others thought of sustainable farming and even more thought about differences in a farm’s scale. We also associated “organic” as something that is healthy, expensive, trendy or alternative in popular culture.

In truth, organic food doesn’t have to be healthier, better for the environment, or even produced on smaller farms than conventional food.

If a farmer wishes to sell her produce as organic, all she has to do is conform to a set of standards put forth by the USDA. This, in turn, allows her farm to be ‘Organic Certified’, and allows her to hike up the price of her produce.

That is not to say the switch-over from conventional farming to organic is simple or in any way easy. Since these standards encompass everything from the chemicals farmers can put on their plants and the way they handle their produce, to the kind of wood they can use for fence-posts and what they feed their animals. Often this process takes anywhere from several years to a decade to complete, and can be quite expensive. (You can read about one dairy-farmer’s switch to organic here.)

III. Commercial Versus Organic

All organic foods are not created equal. Michael Pollan had quite a lot about this topic in his book The Omnivore’s Dilemma, particularly about the differences between large-scale and small-scale organic farms.

In chapter 9, ”Big Organic”, of The Omnivore’s Dilemma, he investigates the difference between what it means to be organic versus big organic. He explores some of the misconceptions of organic food products ranging from those produced at industrial farms such as Earthbound, which can be found in large organic food markets, to food produced by farms like Polyface owned by Joel Salatin in Virginia, that are what Salatin calls “beyond organic.”

In 1990 Congress passed the Organic Food and Production Act (OFPA) in order to establish uniform standards on organic foods and farming. However, since then, there have been many misinterpretations and arguments on the USDA’s standards. For example, the use of synthetics and “access to pasture” continue to be up for debate.

In 1990 Congress passed the Organic Food and Production Act (OFPA) in order to establish uniform standards on organic foods and farming. However, since then, there have been many misinterpretations and arguments on the USDA’s standards. For example, the use of synthetics and “access to pasture” continue to be up for debate.

One of the largest commercial organic farms in the United States, Earthbound, produces 25,000 acres of organic fruits and vegetables. This organic farm eliminates 270,000 pounds of pesticides and 8 million pounds of petrochemical fertilizers (pg164, Pollan) that would have been applied if the same land was farmed in a conventional manner. Their tractors run on biodiesel fuel and the farm is managed with frequent tilling. In order to sell their products at low prices, they must deliver their products to conventional supply chains. Although a large amount of energy is used to deliver their products across the country, they do plant trees to offset the costs of fuel consumption. However, to make an Earthbound packaged vegetable salad, the mechanical processes that are required, including the vegetable washes, refrigerated transportation and manufacturing containers, consume 4,600 calories of fossil fuel energy ( pg 167, Pollan). This means that 57 calories of fossil fuel energy are required for every calorie of food produced. (These figures would be about 4 percent higher if the salad were grown conventionally).

So much for energy efficiency.

IV. ‘Post Organic’; The Jackson Pollock of Farming.

Like Jackson Pollock believed of the painters preceding him, Joel Salatin, who runs Polyface Farm, believes that these organic farmers have rather missed the point. The intricacies and complexity of the system Salatin and his family have created on their farm, as described by Pollan, demonstrate that farming can be an art.

The point, Salatin believes, isn’t for the farmer to conform to a set of standards. Instead, he believes it is the responsibility of the farmer to do the best he can, in terms of environmental conscientiousness and sustainability, with what he has.

Polyface Farm has done this by creating an interwoven conglomerate of systems and food chains, where the waste products of one chain (which would be useless garbage to any other farm) become the inputs and reactants of the next chain. For example, the animal’s waste products, which normally would be thrown away, provide a valuable source of nitrogen for the grass on which Salatin grazes his cows.

The cows produce manure, which fosters grubs to feed the chickens. After the chickens have had their fill, the left-overs are mixed with woodchips and corn, which ferments in an anaerobic process. It turns out pigs really dig fermented corn, and their rooting aerates the compost, killing off the anaerobic bacteria and sterilizing the humus. The end product of this progression is a nutrient-rich muck, which goes right back to the grass so the circle can repeat. This is just one example of the efficiency of Polyface Farm.

V. Conclusions

Buying organic represents a shift in our society toward food consciousness; a desire to know where our food comes from and how it impacts our world. Organic farms and food brokers have met this increased demand in a variety of ways, some better than others. In the end, you will have to decide for yourself whether you should spend a little extra for organic.

Granted, with the various labels and proclamations from the feuding fractions of organic versus post-organic, or local versus natural, it takes a little work to choose what’s best for you, your wallet, and the planet. It may be wise to take a leaf out of Joel Salatin’s post-organic head of lettuce. Basically, do the best you can with what you’ve got, keeping in mind that a little effort can go a long way, both toward the environment, and your satisfaction as a consumer.

Links of interest

For a detailed examination of the organic v. industrial argument, well worth the time: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hVrIyEu6h_E

To answer the question “can Organic food feed us all?”: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q3ciISvqpTo

Work Cited

1. Pollan, Michael. The Omnivore’s Dilemma. 4. Penguin Books, 2006. Print.

Hi all i want to express that i really like this blog, i just google and i found it..

thnaks

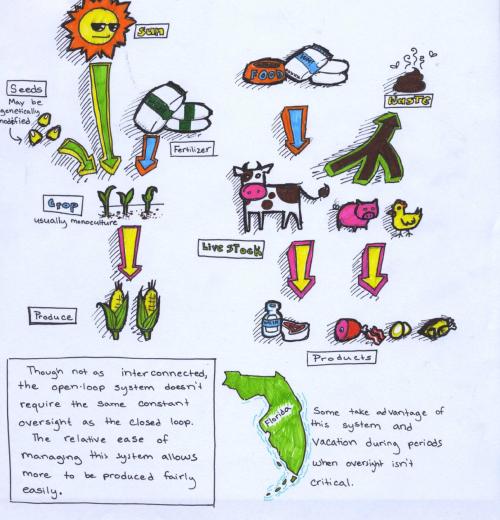

great post! i really like the drawings, they give life to the written words 🙂